The Rising of the Moon

By John Keegan Casey

Rebel ballads have always been an essential part of the Irish songbook. Vast in number, they recount the story of the suppression of Ireland’s quest for freedom by imperial British forces, in all manner of different times, settings and styles – until the mould was finally broken between 1916 and 1921, and the Free State of Ireland, encompassing 26 counties was established. Perhaps the greatest treasure trove of these songs is focussed on the failed Rising of 1798, spearheaded by the United Irishmen, who famously aspired to gather, under the one flag of Irish freedom, “Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter.” It is tempting to ask how different might Ireland be now if they had succeeded. Better by far, however, to relish some of the powerful songs that tell tales of heroic leadership against the greater military might of the British occupying forces. Perhaps the finest of all of these ballads is one that has found favour with many contemporary singers, entitled ‘The Rising of the Moon’. Written by a man dubbed ‘the Fenian poet’, John Keegan Casey, and first published in 1867, it captures vividly the fierce urgency of preparations for the rebellion, and the cry for freedom that – in the long run – could not and would not be quenched.

The Story Behind The Song

It was Theobald Wolfe Tone who devised the name adopted by the United Irishmen. The group met for the first time in Belfast, in October 1791, and agreed on the fundamental goal of “equal representation of all of the people in parliament.” That would involve the extension of the franchise to Catholics, who at the time – under British rule – were the target of an oppressive form of ruthlessly sectarian discrimination. Through the decade, Wolfe Tone’s thinking became more radical. Inspired by the new revolutionary spirit abroad, which saw the old ruling class swept away in France and the establishment there of a Republic, Tone became more ambitious. With that backdrop unfurling, the United Irishmen aimed to overthrow British rule and create a Republic that would be “de-Christianised,” and thereby made equally welcoming for all, irrespective of belief or tradition, uniting Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter.

The story of the decade in which the United Irishmen rose and fell had many twists and turns before – in the month of December 1796 – Wolfe Tone successfully negotiated a planned invasion by a French battalion, comprising almost 15,000 personnel, arriving on 43 boats. They reached the coast of Ireland, but bad weather and rough seas made it impossible for the ships to land, and the mission was aborted. The United Irishmen had the bit between their teeth now and were not for turning. With membership of the organisation reaching an estimated 300,000, it was not a question of ‘If’ there would be a rising, but ‘When?’

In his personal diaries, Wolfe Tone – who had qualified as a barrister – outlined his ambitions in compelling terms. "To subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England (the never failing source of our political evils) and to assert the independence of my country – these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland: to abolish the memory of all past dissensions; and to substitute the common name of Irishmen in place of the denomination of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – these were my means.”

Those means were ultimately destined to fail. Despite having agitated for Catholic emancipation, the United Irishmen were vehemently opposed by the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Meanwhile, a detailed counter-insurgency plan was put in place by the British. When the rebellion of 1798 broke out, changes in command in the French army, and the commitment to a campaign in Egypt, meant that support for the Irish rebellion was far thinner than had been anticipated. A series of three French naval raids were planned along the West and North coast of Ireland. These were met with fierce resistance by the British forces. One French ship, The Hoche, with Wolfe Tone on board, fought the Battle of Tory Island against British forces – and lost. The Hoche surrendered, and Wolfe Tone landed in Buncrana, Donegal, where he was arrested. He was tried for treason and sentenced to death. He is reputed to have died by suicide before his execution could take place. Wolfe Tone has since become recognised as the true founding father of Irish Republicanism.

The failure of the rebellion of 1798 hit hard. The aftershocks included the Act of Union (1801), which abolished the Irish parliament and imposed direct rule from London; and a second Rising in 1803, spearheaded by Robert Emmet, which also failed. Robert Emmet too was executed. Manifest injustices continued, and so did the fight for Irish freedom. The most famous Irish political figure of the 19th Century was the constitutional nationalist, Daniel O’Connell, who became the undisputed leader of the disaffected Roman Catholic majority on the island of Ireland. He was the driving force behind the movement that delivered Catholic Emancipation in 1829, and became known as the Great Liberator. However, any progress he might legitimately have claimed title to hit the rocks with the Great Famine of 1845-1852, which resulted in an estimated 1 million deaths and the forced emigration of 2.5 million Irish people. This created the basis of the Irish diaspora, with numbers in the region of 70 million people across the world now identifying as being of Irish background.

‘The Wearing of the Green’ – which began life as a poem titled ‘Green Upon The Cape’ (from 1798) – is one of the best known songs lamenting the defeat of the United Irishmen. The most celebrated version was credited to the Irish playwright Dion Boucicault, from his play Arragh na Pogue (or The Wicklow Wedding), set during the 1798 rebellion and performed in 1864. It is sung to a traditional Irish melody.

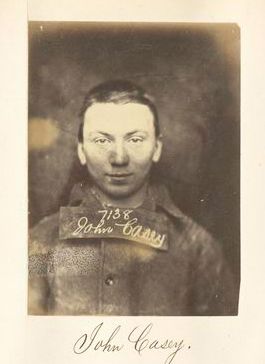

The Fenian Poet, John Keegan Casey, following his arrest by the British authorities

The Fenian Poet, John Keegan Casey, following his arrest by the British authorities

There is no doubt that John Keegan Casey would have been familiar with ‘The Wearing of the Green’ when – at the age of just 15 – he wrote ‘The Rising of the Moon’. It was first published five years later in his book A Wreath of Shamrocks (1866). He used the same melody as ‘The Wearing of the Green’, for a new, and inspirational story of Irish bravery, as the Fenian Movement, of which he was part, geared up for another Irish rebellion in 1867. The song tells the story of how the rising in 1798 unfolded in the area of Granard in Co. Longford. The song never gets to the point of failure, instead conveying the heroic dynamic that was involved in the battle to establish a non-sectarian Republic of equals in Ireland.

“Out from many a mud walled cabin eyes were watching through the night,” the narrative runs, “Many a manly heart was beating for the blessed morning's light/ Murmurs ran along the valley to the banshee's lonely croon/ And a thousand pikes were flashing by the rising of the moon.”

The image is of a brave army of men united together in the righteous pursuit of freedom.

“All along that singing river, that black mass of men was seen/ High above their shining weapons flew their own beloved green/ Death to every foe and traitor, whistle out the marching tune/ And hoorah me boys for freedom 'tis the rising of the moon.”

With its evocation of night manoeuvres of the most dangerous kind, it proved to be a stirring anthem – though it was just one of many that celebrated what came to be recognised as a seminal moment in Irish political history. Later, the songwriter Patrick Joseph McCall (1861-1919) drew on the rebellion for songs that also entered the canon. McCall had penned the epic ‘Follow Me Up To Carlow’ about the exploits of the local chieftain Fiach McHugh O’Byrne, who defeated 3,000 British soldiers in battle in 1580. That song has been recorded by leading Irish groups like Planxty, The Wolfe Tones and The High Kings, among others. But 1798 proved even more fertile ground. McCall focussed on the exploits of the rebels in Wexford in ‘Boolavogue’, written in 1898, to mark the centenary of the rebellion, and again in the rousing ‘Kelly, the Boy From Killane’. But of all the rebel songs, ‘The Rising of the Moon’ – written in a conversational style – can justifiably be seen as the stand-out. It has been recorded by international folk stars like Peter, Paul and Mary, Judy Collins and Barry McGuire, as well as Shane MacGowan, The Dubliners, The Clancy Brothers, The High Kings and dozens more.

Originally from Mount Dalton in Co, Westmeath, John Keegan Casey was arrested and held without trial for his part in the Fenian rebellion of 1867. He was released on the understanding that he would emigrate to Australia, but preferred to stay in Summerhill in Dublin, living in disguise as a Quaker. His health had suffered from his period in jail and he died when he fell from a cab in the centre of the city in 1870. Newspapers reported that between 50,000 and 100,000 people attended his funeral.

'The Rising of the Moon’ is still widely regarded as one of the quintessential Irish ballads.