Over There

By George M. Cohan

Written to inspire young American men to fight in World War I, ‘Over There’ had sold two million copies by the end of the war, and remains one of the most popular songs of that grim era. With Irish song and dance in his blood, George M. Cohan found success as a playwright, actor, composer and producer and became revered as one of the greatest figures ever in American theatre. Thanks to the success of ‘Over There’ – which he described as a ‘marching song’ – Cohan was presented with the Congressional Gold Medal by President Roosevelt for his contributions to World War I morale – an honour which had previously been reserved for military and political leaders, philanthropists, scientists, inventors, and explorers. The most popular version of ‘Over There’ was sung by Nora Bayes. However Enrico Caruso and Billy Murray also released well-known versions, before it was featured in the Oscar-winning biopic of George M.Cohan’s life, Yankee Doodle Dandy.

The Story Behind The Song

George M. Cohan was born in Rhode Island, New England to Irish American parents (when they arrived in the United States, his grandparents had changed their Irish surname from O’Caomhan to Keohane, then Cohan). A showbiz family, Cohan’s father, Jeremiah (Jerry) Cohan and mother, Helen (Nellie) Cohan née Costigan, were vaudeville performers, and as a result the young George and his sister Josie were appearing on stage before they could walk. By the age of seven, Cohan was an accomplished violin player, playing second violin in house orchestras; and, by 13, he’d landed the lead role in the stage play Peck’s Bad Boy.

The family toured State and county fairs as a four-piece known as The Four Cohans, performing songs, dances and sketches, before – attracted by the bright lights of Broadway – they headed to New York. The influence of Irish music on Cohan’s career was immense. His father was an Irish dancer and played the harp, while his mother brought the Irish sense of humour to the stage as a mimic and skit-show actress. At 17, Cohan himself invented an eccentric dance step that revolutionised the buck-and-wing form of tap dancing and became his personal trademark: Cohan, the “song-and-dance” man, was born. Fans of Bob Dylan will remember what the future Nobel Prize winner said when he was asked at a press conference in San Francisco in 1965 if he thought of himself primarily as a singer or a poet: “Oh, I think of myself more as a song and dance man, y’know.” It was a nod to George Cohan. Cohan’s end-of-show routine became another trademark, as he quipped to an enthralled crowd: “Ladies and Gentlemen, my mother thanks you, my father thanks you, my sister thanks you, and I thank you.”

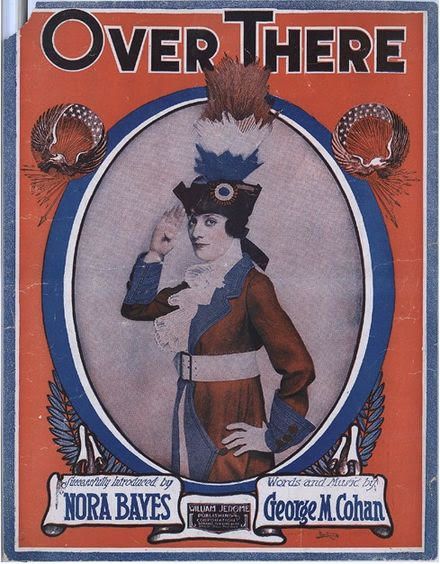

Nora Bayes: she has been described as the Beyoncé of the early 20th Century...

Nora Bayes: she has been described as the Beyoncé of the early 20th Century...

Cohan soon overtook his gentle father Jerry as the leader of the Four Cohans and they prospered, becoming the most successful vaudeville act in America. It would be impossible to overstate Cohan’s status in American music. The New York Times described him as “the greatest single figure the American theatre ever produced – as a player, playwright, actor, composer and producer.” He wrote over 20 musicals – one entitled Molly Malone after the old Irish ballad – and became famous for composing songs like ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’, ‘Give My Regards to Broadway’, ‘Life’s A Funny Proposition, After All’ and the ultra-patriotic ‘You’re A Grand Old Flag’. When he married his second wife Agnes Nolan – one of 18 Irish-American siblings – he moved his new in-laws into a larger home, and bought them a summer house across the street from another large (and larger than life) Irish family, the Joseph P. Kennedy clan.

The day the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, Cohan famously started humming a song set to the sound of the bugle call. By the end of the morning, he had the lyrics, verse, chorus and tune of ‘Over There’, which became a huge hit: the most popular American song of the war era. The first recording, in June 1917, was by The Peerless Quartet. It was also recorded and released in October that same year by American singer and vaudeville performer Nora Bayes, who was already famous for having been the first person to sing the 1908 hit, ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’. She had signed with Columbia Records, and gone on to record over 60 songs over the next six years. Bayes, who has since been dubbed “the Beyoncé of the early 20th century,” was personally chosen by Cohan to record his morale-boosting song. Following its international success, she became the first woman to have a Broadway theatre named after her – the Nora Bayes Theatre – shortly after the war ended in 1918.

‘Over There’ was also recorded by Arthur Fields (famous for his recording of ‘Hunting The Hun’ released in 1918), the great Italian tenor Enrico Caruso (also in 1918), and – much later – Plácido Domingo. Whatever the ethics of the war, ‘Over There’ proved to be an inspiration both to the young men who were being sent to fight and to those keeping the home fires burning. By the end of the war, Cohan’s reputation as America’s greatest showman was cemented. The story of his life – and his lifetime’s work of some 1,000 songs – was condensed into the film Yankee Doodle Dandy to Oscar-winning effect by another Irish-American, James Cagney. The film prominently featured ‘Over There’ – sung by James Cagney, who played Cohan, and Frances Langford – and was released in 1942, shortly before Cohan’s death. The film depicts the presentation by President Roosevelt of the Congressional Gold Medal to George M. Cohan for his contributions to World War I morale – a ceremony which took place in 1940. “Your songs,” the character Roosevelt says to Cohan in the film, “were a symbol of the American spirit. ‘Over There’ was just as powerful a weapon as any cannon, as any battleship we had in the First World War.”

The world might now take a different view of the sacrifices that had to be made by ordinary soldiers in successive World Wars, but Cohan’s reputation remains undimmed. He would become known as The Man Who Owned Broadway – also the title of a biography by John McCabe – and the Father of American Musical Comedy. A friend later described Cohan with the words: “There was never another Irishman born in the world who had his unfailing charm.” It is, by any standards, some claim to fame.

Among many public tributes to the theatrical legend, there is a statue of George M. Cohan in Times Square, New York; a star in the Hollywood Walk of Fame; a bust in Fox Point, Providence, Rhode Island, where he was born; and a street, George M. Cohan Plaza, also in Providence, named after him.