All Things Bright and Beautiful

By Cecil Frances Alexander (1848)

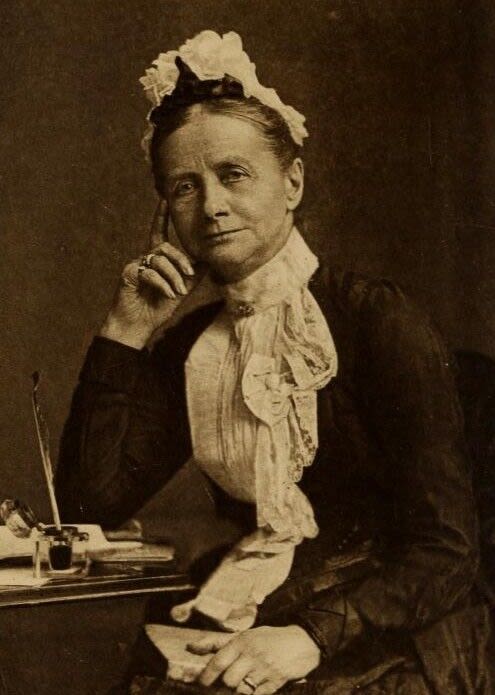

Irish society was, for many centuries, heavily dominated by the Christian religions, especially Roman Catholicism. It’s hardly surprising that the nation produced a sizeable repertoire of Christian hymns. These were usually sung in Latin, but there were also popular hymns in English. The lusty ‘Hail Glorious St. Patrick’ was one of the most popular, with words written to an old Irish melody by a woman known only as Sister Agnes. However, the Irish hymn that made the most lasting impact outside Ireland was ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’, composed by the Dublin born Anglican writer, Cecil Frances Alexander. With 'All Things Bright and Beautiful', she delivered a timeless phrase that has since become part of the secular vernacular.

The Story Behind The Song

Cecil Frances Humphreys (later known as Fanny Alexander) was born in Eccles Street on the Northside of inner city Dublin, in 1818. A member of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy class, she moved with her family to Ballykean House, near Rathdrum in Co. Wicklow, where she lived until 1833. This impressive manor house is now listed by Ireland’s Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media as a place of architectural distinction.

When Fanny was 15, the Humphreys family moved again, this time to Milltown House in Strabane, Co. Tyrone. Here. she is reputed to have written poems in her school journal, thus beginning what was an impressively successful career as a writer.

Inspiration for the hymn that was to make her name was drawn from several sources, including Psalm 104 in the Old Testament, in particular Verses 24 and 25. Echoing the general message of the Psalm, that God made everything, including all the wonders of the natural world, ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ clearly espouses a creationist view of the universe in line with Christian teaching. However, it was also – consciously or otherwise – influenced by Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Coleridge's observation that “He prayeth best who loveth best / All things great and small” is echoed in the second line of Fanny Alexander’s chorus: “All things bright and beautiful/ All creatures great and small…”

Fanny Alexander visited Markree Castle in Sligo and many assume that the beauty of the surrounding gardens inspired her lyrics. However, she was also a regular visitor to Bellarena House in Co. Derry. In 1973 Sir John Heygate insisted that the reference to "the purple-headed mountain" and "the river running by" in the hymn were inspired by the area surrounding that house. The melody most commonly associated with her words is believed to have been written by William Henry Monk (1823-1889).

Alexander’s lyrics for ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ were first published in her collection Hymns for Little Children (1848). The book became so popular that – at the last count – it had run to over 69 editions. In modern publishing and songwriting parlance, it would be referred to as “the pension”, for the way in which it has retained popularity and interest and earned the writer ongoing royalties. With references to “All creatures great and small,” it’s easy to see how the hymn would have appealed to children as well as adults. Indeed, it was so widely admired that it was also adopted by adherents of other Christian denominations.

Fanny Alexander became a revered figure as a composer of hymns. She also penned such popular works as ‘There is a Green Hill Far Away’ and ‘Once in Royal David’s City’. Renowned literary figures Mark Twain and Alfred Tennyson were fans of her work, and the 19th century French composer Charles Gounod said that – in the simplicity of her words – “her poems set themselves to music.” Her work has proved to be of enduring value, and the current Church of Ireland hymnal includes six of her songs.

She collaborated with Harriet Howard on such religious publications as Verses for Holy Seasons and the Lord of the Forest and His Vassals in the 1840s. Then, in 1850, she married William Alexander, a Protestant clergyman from Derry. They settled in that part of Ireland, where he was appointed bishop of Derry and Raphoe, and later became the Anglican Primate of Ireland. They resided variously near Castlederg in Co Tyrone, in Upper Fahan in Co Donegal and in Strabane. Although some may argue that he was overshadowed by his wife’s fame as a hymn-writer, William Alexander has the distinction of being mentioned as part of the procession in the Cyclops section of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Alexander was six years younger than Fanny. She was financially independent, not only because of her very substantial book earnings, but her father had also created a trust for her of £3,000, a very substantial amount of money at the time, worth approximately £300,000 now.

Fanny used the money earned from sales of her books to help fund a number of charitable works. Her compassion for disadvantaged citizens was demonstrated in her willingness to travel several miles each day, calling to both Protestant and Catholic homes to visit people who were sick or mired in poverty, bringing them food, clothes, and medicines.

It’s interesting to note that she and other women were writing hymns and achieving considerable levels of public attention in an era when women could neither vote nor own property.

Cecil Frances Humphreys died from a stroke in 1895 at the age of 77, and was interred in Derry in a hillside cemetery that was thought to be the actual inspiration for her hymn, ‘There Is A Green Hill Far Away’.

The words of her most famous hymn later attracted criticism and controversy, for its apparent endorsement of inequality. The third verse ran:

“The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them, high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.”

In truth, however, those lines do nothing more than give expression to the obvious and irrefutable implication of living under, and accepting a monarchy – all the more so when the King or Queen is also the head of the Church, as in the Anglican tradition.

When The English Hymnal was published in 1906 that verse was discretely omitted. The more recent Hymns Ancient and Modern (1950) did likewise. But those who have argued that ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful' was intended as a repudiation of Charles Darwin’s On The Origin Of Species are wrong, simply because her lyrics were published a decade before Darwin’s ground-breaking work.

Controversial aspects notwithstanding, the hymn not only survived but gathered popularity at home and abroad. The best-selling British vet and author, James Herriott, lifted the titles for American editions of his early works from Fanny Alexander’s most famous song, calling them respectively All Creatures Great and Small (1972), All Things Bright and Beautiful (1974) and All Things Wise and Wonderful (1977). There have been numerous film and TV adaptations of his books – including a film All Creatures Great and Small; a BBC TV series of the same name, which ran for 90 episodes in the 1970s and the 1980s; and a Channel 5 series also called All Creatures Great and Small, that ran for 12 episodes over two seasons – further cementing Fanny Alexander’s song in the collective imagination.

Cecil Frances Humphreys is not the only songwriter to turn to the Psalms for inspiration. The works of Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave have all been linked to the original David. Perhaps the best known musical explorer of the Psalms is Bono of U2, who turned Psalm 40 into the final song on the band’s breakthrough album War (1983), using the title '40’. It was the song with which U2 closed their concerts on the War tour – and many more since.

‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ continues to attract fresh modern interpretations by a diverse range of artists, including Welsh crossover singer Katherine Jenkins, The Cambridge Singers, who recorded a popular version with the City of London Sinfonia, and the Atlanta Masters Chorale in the USA. There's even a karaoke version by Gilbey Aguirre.